Do you like sewage? If the answer is yes then aren’t you in for a treat! In the second of our Innovation Stories series, we have Sir Joseph Bazalgette, and this one is a two-parter! A now somewhat controversial figure, was his work for good… or ultimately for bad?

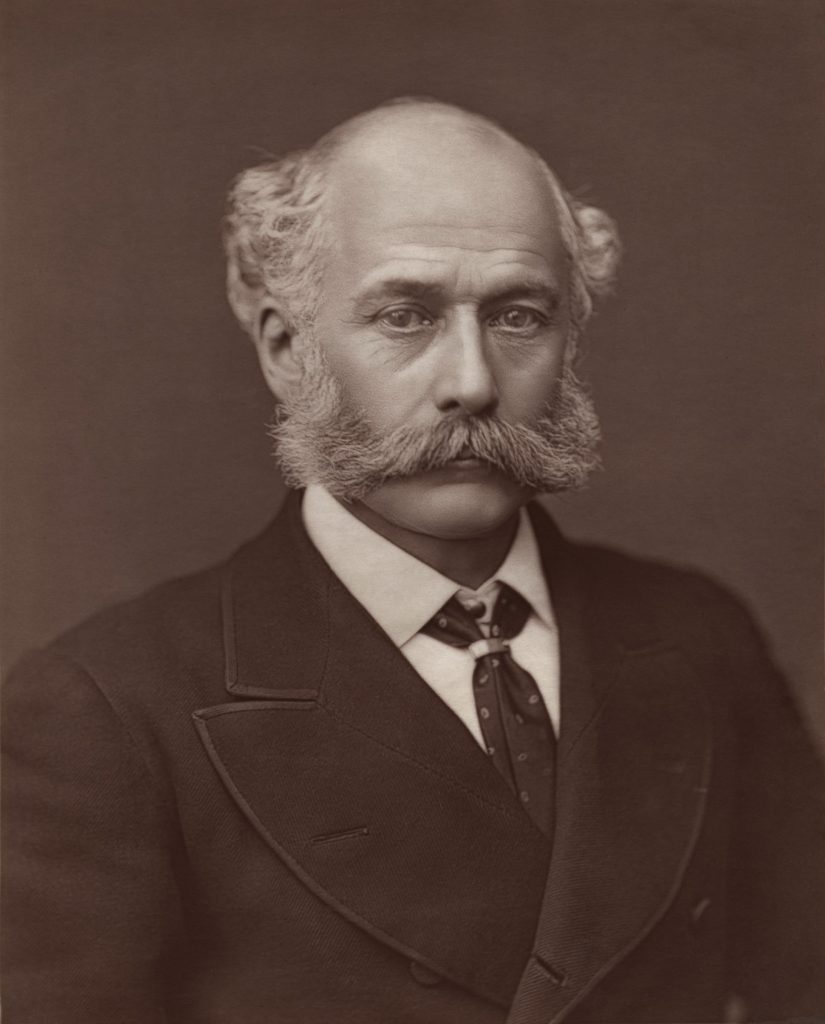

Part one of this blog is in defence of Sir Joseph Bazalgette, the father of London’s sewer network:

In the summer of 1858, London was choking on the “Great Stink”—a foul crisis that turned the Thames into a toxic soup and triggered deadly cholera outbreaks. In fact, the stink got so bad that parliament (which is located on the banks of the river Thames) passed a bill to come up with a solution to the problem. How had this happened? Well before this time there was no sewerage in London – all human effluent and waste was collected by London’s ‘Night Men’ (see image below) who collected the waste from your house or street – or alternatively dumped it into the nearest river or stream.

Enter Sir Joseph Bazalgette, a visionary civil engineer who transformed the city’s future with one of the greatest public health feats of the Victorian era. As Chief Engineer of the Metropolitan Board of Works, Bazalgette designed and built a revolutionary sewer system: over 83 miles of intercepting sewers, embankments, and pumping stations that redirected waste far from the city. His work not only cleaned the Thames but also saved tens of thousands of lives and laid the foundation for modern urban sanitation.

Bazalgette famously overbuilt the sewers to accommodate future growth—proof that foresight saves lives. His sewerage system is still in use today – had he not had this foresight the network would have been overrun decades ago.

However, his solution was by no means perfect – his solution did not initially incorporate a sewage treatment works – it was simply poured into the Thames further out of the city nearer the sea. It wasn’t until 1878 when a pleasure vessel carrying day-trippers capsized in the middle of a sewage outflow and many died that the water started to be treated. And this isn’t the only reason to think that maybe his innovation did more harm than good – in Part 2 we’ll highlight the Prosecution – why his pinnovation in fact held back sanitation – and why we are still living with it’s consequences today.